Systems Strike Ukraine with Amplification and DrDoS Attacks

A10 Security Research Team Tracks DDoS Attacks

By Paul Nicholson and Rich Groves

The conflict in Ukraine has brought specific focus on state-sponsored cyber threats, in addition to the physical confrontation. Immediate actions are required to disrupt attackers targeting Ukrainian-based systems, and the associated attacks and impacts elsewhere. Organizations need to act now.

In this blog, we detail new findings on specific DDoS attacks observed by the A10 security research team. We offer advice on how to take action to mitigate these attacks, and ensure your networks are not an unwitting attacker.

Reports and Guidance on the Threat Vectors

State-sponsored attacks are not new, but arguably, they have been in the background in the last few years. More general businesses in sectors such as banking, healthcare and government entities have been targeted by distributed denial-of-service attack and have featured prominently in headlines. The current cyber conflict is being waged across many different fronts. Recent reports have included malware, DDoS attacks, and website defacement via advanced persistent threat (APT) actors. Guidance from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), part of U.S. Homeland Security warns of the threat at hand:

“Further disruptive cyberattacks against organizations in Ukraine are likely to occur and may unintentionally spill over to organizations in other countries. Organizations should increase vigilance and evaluate their capabilities encompassing planning, preparation, detection, and response for such an event.”

Today, we may be seeing the results of preparation for the current cyber conflict. For example, in 2020, it was revealed that the Russian FSB was seeking to build a massive IoT botnet. We also have seen reports of malware such as Wiper, with multiple variants, inflicting damage by removing confidential data from targeted computer systems.

In addition, distributed denial-of-service attacks, likely state-sponsored, are targeting government, banking and education services, effectively, organizations that serve everyday people. We are also seeing reports where counter attacks by hacktivists are happening. For example, the hacking of prominent Russian websites to post anti-war messages from the group, Anonymous, have occurred. This is clearly demonstrating that there are measures and countermeasures being taken, offensively and defensively.

DDoS Amplification Attacks and Distributed Reflection Denial of Service Attacks (DrDoS) are Targeting Ukraine

From our A10 security research team systems, we’ve witnessed significant and sustained attacks on Ukrainian government networks, and by connection, commercial internet assets, with a massive spike on the first day of the conflict.

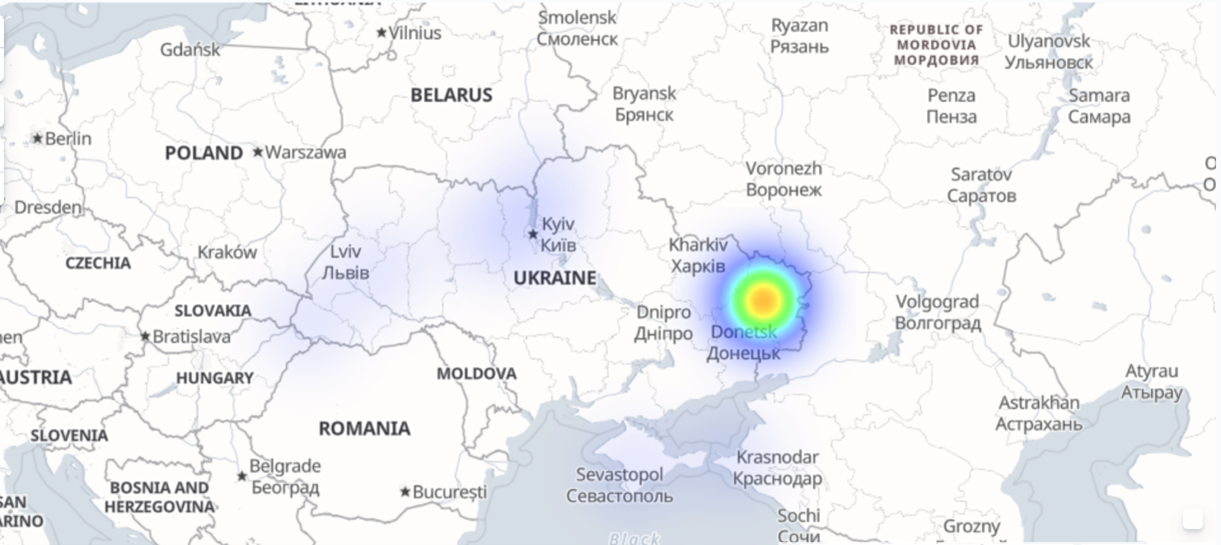

Figure 1: Heat map showing DDoS attacks on Ukraine.

Investigating one of our research honeypots, focusing on the first day spike, we can see that hackers are attempting to co-opt legitimate systems into a coordinated DDoS amplification attack and distributed reflection denial of service attack (DrDoS, a.k.a. reflection attack). The honeypot host in question was first attempted to be co-opted a few hours after the physical confrontation started in Ukraine on February 24. We then saw more activity a few hours later. As shown in the heatmap in figure 1, which has been filtered by responses requested targeting systems in Ukraine, we can see many targets. However, two stand out from this first day:

- PP Infoservis-Link – with over two million Apple Remote Desktop (ARD) requested responses

- Secretariat of the Cabinet of the Ministers of Ukraine – with over 600,000 Network Time Protocol (NTP) requests

Note, we refer to the above as the first and second targets, respectively, below.

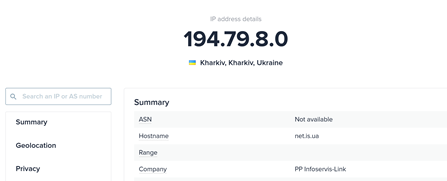

The first target is somewhat obfuscated by the name returned from the automated look-up. On drill down on PP Infoservis-Link, we can see it relates to an IP address block of 194.79.8.0. Checking where this was assigned to, we can see that one source lists this as geolocated to one of Ukraine’s largest cities – Kharkiv, while the whois information shows it as Severodonetsk, Luganskiy region, Ukraine, in Luhansk.

Flooding the block, while not a specific host, still creates a DDoS attack that must be dealt with by the networking equipment, unless it’s mitigated upstream. Thus, we can conclude this is aimed at affecting many applications, servers, and core infrastructure served by that block and equipment.

The second target, a government department, appears as an obvious potential in a state-sponsored campaign, as described from Wikipedia:

“The main objective of the Secretariat is the organizational, expert-analytic, legal, informational, material-technical support for the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, government committees, the Prime Minister of Ukraine, the First Vice-Prime Minister, Vice-Prime Ministers, the Minister of Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, and ministers without portfolio.”.

Figure 2: Location information from ipinfo.io https://ipinfo.io/194.79.8.0#block-summary lookup.

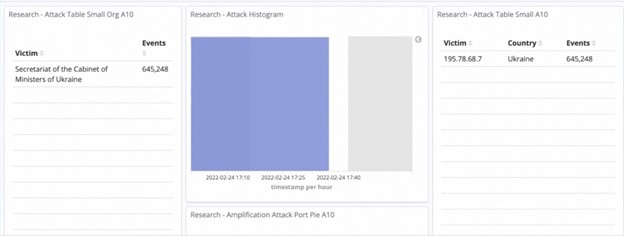

Figure 3: 645,248 amplification request attempts to a single honeypot in 15 minutes.

Delving into these attacks, we can see that they were similar, but not identical. For example, the second target was targeted by a network time protocol (NTP) request for the DDoS amplification attack and distributed reflection denial of service attack (DrDoS, a.k.a. reflection attack) on UDP port 123, which is quite common, while he first target had requests with the less common Apple Remote Desktop (ARD) protocol on UDP port 3,283.

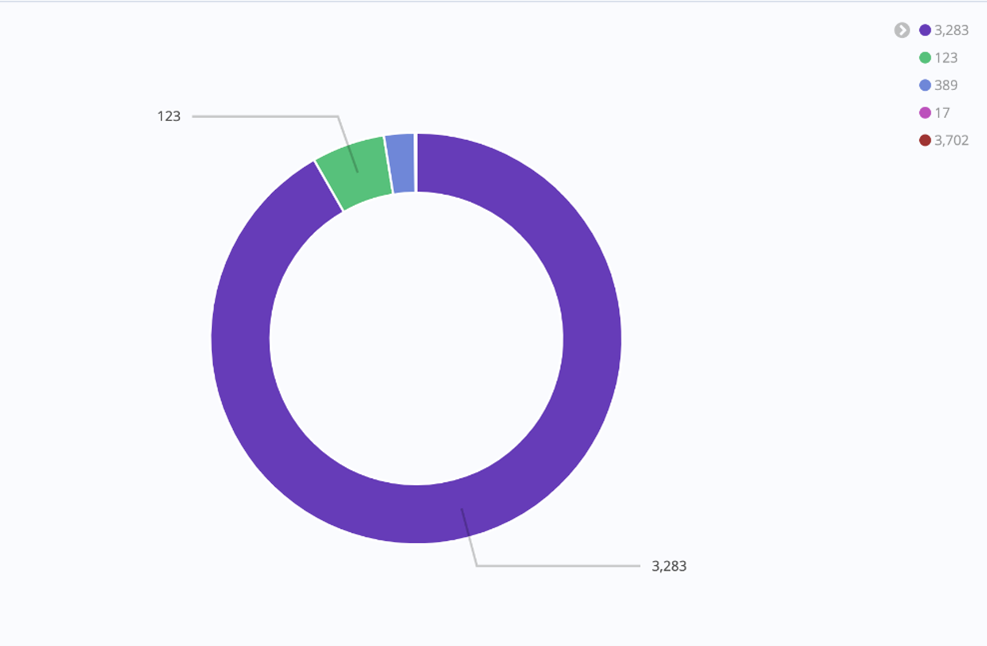

Figure 4: Protocols targeting Ukrainian registered ASNs by UDP protocol on February 24, 2022 to a single honeypot. ARD, NTP, and CLDAP are the most requested, respectively. Over the next six days, NTP became the largest protocol observed on this same honeypot after the first day spike.

As these are UDP ports, they are connectionless (versus connection-orientated with TCP), enabling the spoofing of the source address, masking the original requestor and, at the same time, reflecting the response to the designated victim receiving the larger, amplified payload. This is why amplification attack and distributed reflection denial of service attack (DrDoS, a.k.a. reflection attack) techniques are preferred by attackers. ARD, for example, can have an amplification value of over 34 times the original request.

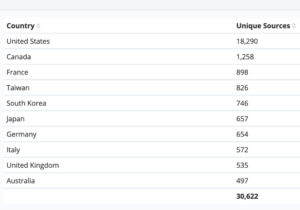

For the ARD attack against the first target, we estimate the majority of the packets requested were 370 bytes (70 percent). However, with many 1,014-byte packets (23 percent), we can calculate an average at around ~500 bytes. If we calculate 500 bytes times 2,099,092 requests it comes to 1,049,546,000 bytes, or just over 1 gigabyte, all requested from one machine. In the A10 DDoS Attack Mitigation: A Threat Intelligence Report, neither of these protocols are in the top five reported. From our research, there are 30,622 potential distributed denial-of-service weapons for ARD that we track. Using just 10 percent of these could theoretically generate 3.2 terabytes of traffic and using 50 percent could generate 16 terabytes of traffic.

Figure 5: Top-10 locations of ARD UDP potential DDoS weapons we track by country, and overall total (which also includes countries not listed).

Cross referencing the ARD protocol identified against the first target in the cyber-attack, we can see there are 30,622 weapons tracked by A10, but with 18,290 (59 percent) based in the United States. While there are many such weapons, this clearly illustrates that IT departments outside of the combatant countries can be actively brought into cyber conflicts. If action is taken, these organizations can directly help minimize the damage to Ukraine. The honeypot we are analyzing was based in the United States.

As indicated above, the two examples spotlighted on February 24 were of an extremely large scale. However, we have seen a consistent level of smaller attacks continue against targets in Ukraine from a variety of UDP protocols. The mix has been changing over time. ARD was dominant on the first day and NTP was dominant over the next six days. Thus, it is imperative for system owners to monitor and ensure their systems are not abused for cyberattacks, illegal actions, and negative purposes.

DDoS Protection for Your Organization, Avoid being an Unwitting Attacker

What good does revealing this type of information do? It clearly shows that many organizations worldwide may have services that are contributing to attacks on Ukrainian digital infrastructure. While these are not intentional as they are legitimate systems that have been manipulated into becoming DDoS weapons, IT professionals should look at their systems and act, using all their tools, not just DDoS protection systems.

Steps to address this issue can include:

- Turning off any non-essential services that might generate potential attacks

- Investigating unusual traffic flows from their organizations around these protocols which could be used in amplification attacks and distributed reflection denial of service attack (DrDoS, a.k.a. reflection attack), specifically UDP services (e.g., traditional protocols like DNS, NTP, etc. and less common protocols like ARD, CLDAP, etc.)

- Turn on available access controls on firewalls and networking equipment to prevent systems from being weaponized

- Ensure all systems are patched and up to date to combat known CVEs

- Review guidelines from multiple sources: CISA, vendors, and other security resources to keep up to date on the evolving situation, and then take steps to ensure systems are secure

- Check that procedures are in place in the case of cyberattacks, particularly when DDoS attacks have often been used as smokescreens to distract for other attacks

Specialized DDoS protection systems like A10’s Thunder® Threat Protection System (TPS®) also provide an enhanced level of protection, specifically enabling techniques to mitigate these attacks, such as actionable (large-scale) threat lists pulling from multiple threat databases, traffic anomaly inspection, finding traffic baseline violations, using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), and more.

It is important to note that organizations should cross reference multiple observability and reporting capabilities to get a comprehensive picture of the network status to ensure the previously mentioned anomalous behaviors are thwarted.

Larger and More Frequent DDoS Attacks Illustrate Action Should be Taken Now

The examples above illustrate that DDoS amplification attacks and distributed reflection denial of service attack (DrDoS, a.k.a. reflection attack) continue to be fast, cheap and easy to perform. Evidence from the A10 DDoS Attack Mitigation: A Threat Intelligence Report, points to a new record for the largest reported attack when Microsoft reported in Jan 2022 a 3.47 Tbps and 340 million packets per second, breaking last year’s record.

This brings home the scale these coordinated attacks can be. It also shows that attacks can potentially be much larger. Microsoft mitigated these attacks by being prepared, both to detect and mitigate these attacks. Increasingly, organizations are falling into the prepared and unprepared categories. Unprepared organizations are the ones more likely to make the headlines or contribute to the spread of problems.

Increased public reporting and visibility will lead to more awareness of cyber threats and will help the IT and security communities better plan to mitigate threats and limit disruption. As an example, the 2016 Mirai distributed denial-of-service attacks increased awareness and caused defenses to be shored up, resulting in some of the successful mitigations we see today.

Summary – Be One of the Prepared with the Right DDoS Protection in Place

By taking the above actions, organizations can help ensure that they are not inadvertently aiding bad actors in disrupting internet services and other critical infrastructure in Ukraine. As illustrated from our threat research, we know certain organization types and regions have been targeted. Due to this changing threat landscape, it is also advisable for organizations in sensitive sectors worldwide, whether government, military or critical commercial infrastructure to reassess their services to ensure adequate defenses are in place to avoid being an unwitting participant or a targeted victim.

As always, A10 DDoS protection customers have access to our DDoS Security Incident and Response Team (DSIRT) in the event of a live attack to assist and if you have questions for the A10 threat research team, please contact A10.

As a global community, what’s happening in Ukraine affects all of us and we hope for a quick return to peace and democracy. We stand by the citizens of Ukraine in these difficult times.